There's history in our homes

You share experiential DNA with everyone who lived in your house before you

By all accounts, Carl Reierson lived a traditional Midwestern lifestyle. In 1910, he married his girlfriend, Selena, who would remain his wife until his death in 1967. In 1913, he bought a photographic studio in downtown Madison, Wisconsin that he operated until he retired in 1953. He attended Luther Memorial Church and was a member of the Knights of Pythias, a fraternal organization dedicated to “loyalty, honor, and friendship.”

Normally, the community’s memory of Reierson would wash away with time. People live pedestrian lives, leave family behind, and their legacy is carried on by their progeny.

But I have a special connection to this man I never met:

We shared the same house.

With the aid of modern searchable newspaper databases, I was able to piece together the history of the people who lived in the same house I now inhabit.

When I tell friends I have done this, they make a face as if I just asked them if I could borrow their underwear for 20 minutes. Each has called this endeavor “creepy,” as if I was summoning the ghosts of dead people who once wandered through the rooms of my home.

But I think it’s fascinating that I have shared experiences with two married people, each of whom was born in the 1800s. Most likely, Carl and Sally ate their meals in the same room I do. My children are growing up in the same bedrooms as theirs. At night, I lay my head in the same spot as Carl did in the same master bedroom.

Historians often think about the history of buildings in terms of large, public structures. Shelves are full of books documenting the birth of the Brooklyn Bridge, Independence Hall, the St. Louis Arch, and the like.

But our homes are just as historic. If you live in a house or apartment over 50 years old, think of all the stories known only to the walls of your abode. Individual family dwellings are where the overwhelming amount of American history is made, but the events that take place in our homes are often left unrecorded.

Online newspaper archives, now available to anyone with a computer, can help us retrieve some of those stories. Back in the day, if an individual was named in a news article, their address was typically listed. This practice would now be condemned as “doxxing” - in the past, it was simply a way a city’s residents kept track of what was going on in their neighborhood.

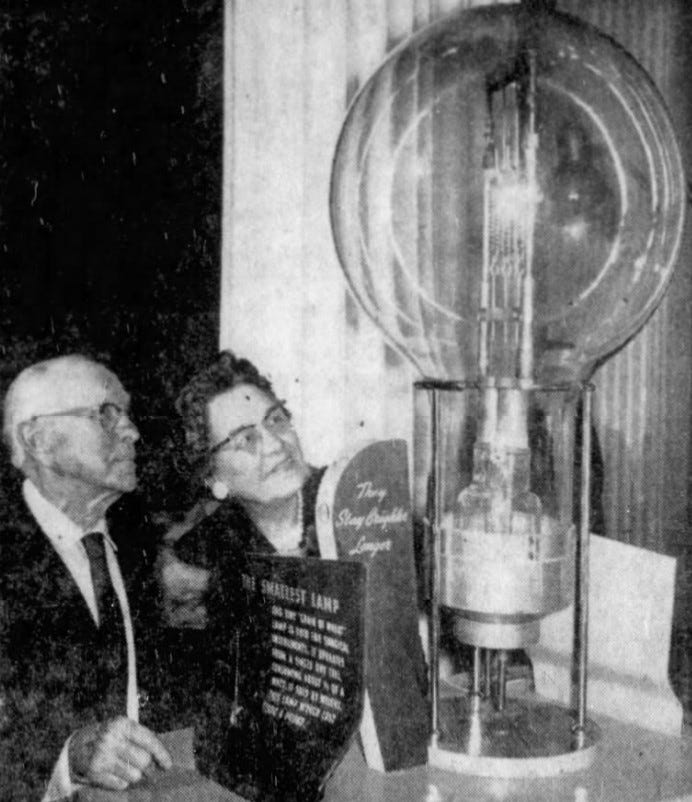

So plugging your address into Newspapers.com, for instance, can yield stories of people that shared your home. Such a search led me to this photo of Carl and Selena (known as “Sally”) in 1961 staring at a giant light bulb during the Wisconsin Power and Light stockholders’ meeting.

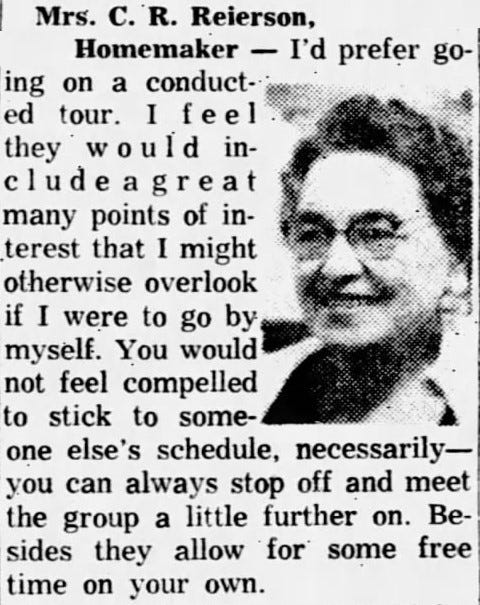

In 1958, Sally was stopped on the street and asked if, when on vacation, she prefers self-guided tours or seeing sights with a tour guide:

Sure, these articles aren’t detailed accounts of the goings-on in my house; but now I can see what Carl and Sally looked like. I can envision them playing gin rummy in my living room.

Why should we care about the people who lived in our homes before we were even born?

One should ask that question of anyone who visits any historical site around the country. Why do we visit Ford’s Theater or the battlefield at Gettysburg or the Alamo in San Antonio?

It’s because we want to experience what the people in the theater experienced the night Abraham Lincoln was felled by John Wilkes Booth. We want to experience with our own eyes what soldiers in the Civil War or the Texas Revolution endured. A firsthand glimpse helps us understand how those events shaped who we are today.

On a smaller scale, our dwellings give us the same opportunity to see how people of the past lived, only more immediately. In many ways, single family homes craft our current day-to-day lives. Homes are living things; oftentimes our daily activities are influenced by design choices made by former residents 50 or 100 years ago.

This is why I feel a kinship with Reierson - the way we moved through life is likely similar based on our common home. Did he and Sally keep tabs on the neighborhood through the giant window in the front of the house as I do? Did they measure the growth of their children on the same door jamb we did? Did they stand in the same spot in the kitchen waiting impatiently for their water to boil?

Did they learn about, say, the shooting of John F. Kennedy while sitting in my living room? Were they happy when hearing about a child’s wedding engagement or sad about hearing of a relative’s death while resting in my bedroom?

All of these experiences become part of a home. Our relatives pass down physical DNA, but former home residents pass down experiential DNA.

The idea that your home changes who you are isn’t a very American one. As George Carlin said, Americans tend to think of their homes as little more than a place to keep their “stuff.”

But South Asians feel a home really does influence who you are as a person.

“People and the places where they reside are engaged in a continuing set of exchanges,” wrote author William S. Sax in a book about Hindu pilgrimages. “They have determinate, mutual effects upon each other because they are part of a single, interactive system."

In an interview with Julie Beck of The Atlantic, Sax said most Westerners believe that "your psychology, and your consciousness and your subjectivity don't really depend on the place where you live.”

“They come from inside -- from inside your brain, or inside your soul or inside your personality," Sax told Beck. “But for many South Asian communities, a home isn't just where you are, it's who you are,” Beck added.

So if a home makes me part of who I am, and if someone else lived in the same home, is it a stretch to assume the home’s former residents and I share a little part of each other?

Plus, learning your domicilic (not a word) ancestors could lead to some surprising discoveries - there may even be a monetary benefit for people who trace their home’s lineage.

How many people living in New York City apartments are unaware they are living in a space once occupied by, say, Miles Davis? What if you knew your home in Omaha, Nebraska was where Marlon Brando once lived? Will the next resident of this apartment at 222 E Pearson St. in Chicago know they will have the same address once used by a young boy named Orson Welles?

But mostly, it’s just cool to think about the people who were there before you.

Reierson died in 1968, at the age of 80. Sally lasted until 1978, dying at the age of 90. Each of their obituaries make it clear they did not die in my home. (If they had, I would not want to know.)

A number of families moved through the house after Sally’s death and before I purchased it in 2001. I can only imagine the episodes of heartbreak and joy that have taken place under this roof. Even if the people are no longer here, the memories belong to the property - and now I am just another part of them.

And someday, it will be someone else’s turn to be changed by the choices I have made.

ALSO: Last week I wrote a piece for Discourse Magazine about the right receiving criticism for its newfound love of laws that provide “bounties” to private citizens who report other citizens for exercising certain constitutional rights (having an abortion, for instance.)

But as I note, the idea of crowdsourcing enforcement of laws infringing on our rights began with progressive administrators on college campuses:

Nowhere is this more evident than in our major colleges and universities, the overwhelming majority of which have set up “bias response teams” to police campus speech among students and faculty. These systems allow students to anonymously report one another for saying or doing anything that makes the offended student blush, even if it happens in a private conversation. The only criterion to report another student to the administration is that some act of “bias” has occurred.

In the schools’ eyes, bias response teams were necessary because old-fashioned university speech codes were being thrown out by courts all throughout the 1990s and 2000s. In the 1980s, major universities began enforcing limits on what students could say, citing the need to dissuade “hate” and “harassment.” Some schools even banned “inconsiderate jokes” and “inappropriately directed laughter.” Most of these speech codes were struck down as violations of the First Amendment.

But the demise of formal speech codes came at the same time student sensitivity to “microaggressions” and “triggers” was rising. So schools that could no longer regulate speech directly began outsourcing the desired regulation to anyone with a smartphone or email account.

Under this scheme, there is no central administrator on campus who has the job of policing public and private utterances. So, schools argue, the bias response team isn’t an official speech code; it simply provides students the opportunity to express their displeasure with other campus members. Further, the schools argue, there is rarely any penalty for expressing a disfavored opinion on campus. The bias response team is simply a clearinghouse that allows a university to understand what is happening on campus.

Read the full story here.

ALSO: For The Bulwark, I wrote another piece discussing the erosion of society’s “unwritten rules,” and how will be poorer as a culture when they go away.

A sampling:

Society has its unwritten rules, too, of course—mores, etiquette, manners, taboos, and other conventions. They are the cartilage between the bones of law and government that allow us to function freely without our every daily interaction becoming fodder for lawyers and lawmakers. And like baseball’s unwritten rules, they have their critics—commentators who consider them relics of the past, where obstinate (white) men handed down guidelines for everyone else to follow. Sticking with the unwritten rules today, the critics often suggest, slows social progress.

But consider the disastrous effects when citizens grow hostile to society’s unwritten rules. Comedians are attacked onstage for telling jokes. Supreme Court decisions are leaked in an apparent effort to pressure justices to either change their vote or hold firm on their position. Regular citizens are mocked and pilloried for their decision to continue to wear masks after the COVID-19 threat has largely subsided.

…

Particularly troublesome is the idea that society’s “unwritten rules” are somehow arcane and thus don’t apply to contemporary society and that they impede progress. Nothing could be further from the truth.

The unwritten rules—whether enforced by religion or parental pressure or by community standards or some other means—are necessary for progress. The unwritten rules that govern sportsmanship, comity, and decency stand to benefit society’s marginalized people the most. Written laws can be enacted that spell out certain formal interactions, especially interactions with the state, but also matters of discrimination in employment and the like. But social progress depends in large part on the presence of, and evolution of, unwritten rules regarding the scope and nature of social interactions. The unwritten rules—understanding, a sense of fairness—have paved the way forward.

Traditional liberals should find themselves horrified by this new thirst for every one of our personal interactions to be monitored by nosy politicians. But the less people know how to interact with one another, the more the government has to step in and provide a framework to guide common human encounters.

There was once a political philosophy that recognized the importance of a society beyond the reaches of government. It recognized the government’s right to protect the conditions of life and liberty, but otherwise left people alone to navigate their interpersonal connections without interference.

This philosophy was called “conservatism.”

Read the full article here.

ALSO: If you want to hear me talk about new albums by recent bands, your prayers have been answered. Last week, I joined the Will’s Band of the Week podcast to review albums by The Smile (a Radiohead side project), Korean guitar pop band Say Sue Me, and fey veterans Belle & Sebastian.

Listen here.

SONG OF THE WEEK: You know how you’re halfway through a song and can’t wait to start it over again? That’s this song.

The Poetics of Space - by Gaston Bachelard, a book you may like.