A publicly-funded arena plan that actually worked

Milwaukee's new downtown arena is a big money generator for the state

Nothing roils a community like a professional sports team threatening to move unless taxpayers pony up for new venue. Progressive community activists decry prioritizing the desires of millionaire owners and athletes over the needs of school kids and soup kitchens. Conservatives point out that billionaire owners can usually afford the expense without plowing millions of taxpayer dollars into such extravagances.

Such was the case back in 2015 when then-Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker supported a plan to spend state money on a new arena for the Milwaukee Bucks. At the time, the Bucks were a moribund franchise threatening to move if it couldn’t replace the thirty-year old Bradley center in the city’s downtown. And the state stepped in to keep them.

The new Bucks owners, Wisconsin state government, and the Milwaukee-area government put together a plan that required the owners to fund $250 million of the new arena, with the government backfilling the rest.

As a columnist for the Milwaukee newspaper, I supported the plan at the time. But I offered my most vocal support over at National Review Online, a place where I knew my arguments would get a frosty response. (The following day, my friend Ramesh Ponnuru offered a gentle riposte.)

The argument by arena proponents went something like this: The state was committing to pay $4 million a year over the span of 20 years, for a total of $80 million. But the state brought in $6.5 million from income taxes levied on athletes who played in the arena - revenues that would have evaporated had the Bucks moved to another city. We dubbed this the “jock tax.”

Further, of that $4 million annual payment by the state, a quarter of it would be offset by a $2 per ticket surcharge on events held in the new arena, which would lessen the state’s contribution by about $500,000 per year. (Other revenue streams included a parking garage and some existing local revenue sources granted to a downtown entertainment district board.)

The numbers told the story - the state actually came out ahead by having the Bucks stay. The team brought in more revenue to the state than the legislature would have to pay out in annual subsidies. If the team were to move, the state would lose this extra cash.

Writing in the Journal Sentinel, I added this tidbit:

And considering the NBA's salary cap is expected to balloon in future years, that will mean that $6.5 million number is low — when all the receipts have been tallied, the state expects to take in almost $300 million on its $80 million investment. And that $300 million doesn't come from poor schlubs like you and me — it's straight from millionaire NBA players. Kevin Durant is about as much a member of the "public" as I am a small forward for the Oklahoma City Thunder.

Seven years later, the numbers are in. And they show the arena has been a resounding success.

According to figures I recently obtained from the nonpartisan Legislative Fiscal Bureau, over $14 million per year is now pouring in from taxes on NBA salaries - well over the $4 million the state is paying for Fiserv Forum.

In other words, if the team had bolted in 2015 for, say, Seattle, state government would be out $10 million per year.

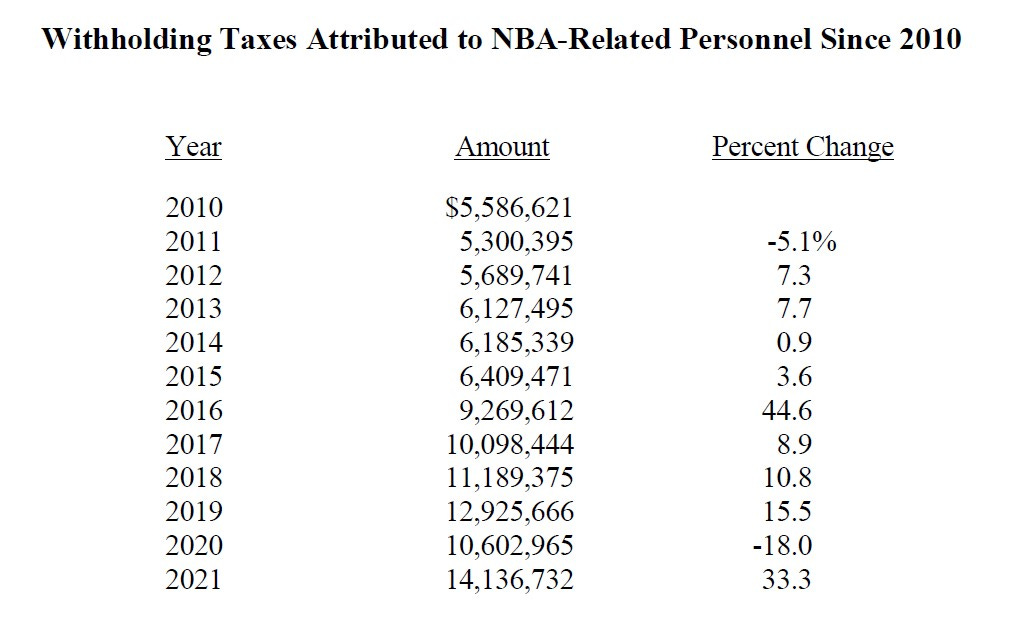

Here’s a table adding up all the tax revenue attributable to the Bucks over the past decade:

This increase wasn’t at all unanticipated. Scott Walker himself pitched a plan called “Cheaper to Keep Them” that projected state revenue from NBA salaries to increase to $25 million by 2034.

But it means the projections are at least on pace, and maybe even slightly ahead of where analysts thought they would be.

The Fiscal Bureau noted that the dip in 2020 was due to the coronavirus forcing the NBA to move to a “bubble” in Orlando, Florida, for the last third of the season. Visiting players are only taxed on games they play in Wisconsin; moving a portion of the season to Disney World caused revenues to drop 18 percent between 2019 and 2020.

But with the salary cap going up and more television money being pumped into the NBA, Wisconsin is now raking in twice the total arena-related tax revenue per year than it was in 2015 when the stadium deal was inked. And that extra money isn’t going to millionaire athletes - it is being sent to elementary schools, police forces and other public services.

Of course, those revenues simply reflect the measurable growth in economic activity. Those who follow the NBA know the Bucks went on to win the NBA championship in 2021, bringing tens of thousands of fans to downtown, all of whom spent money in newly-created restaurants and bars. One of the highlights of the playoffs last year was seeing a throng of nearly 100,000 fans of jersey-wearing fans outside the arena cheering the team on. (That delightful scene was marred this year when, following a playoff game, gunfire broke out just outside the “Deer District.”)

If any part of the 2015 arena plan has fallen short, it is the amount of revenue expected from the per-ticket service fee. Amid COVID, ticket fee revenues dropped to $230,000 in 2020, recovering slightly to $355,000 in 2021.

The success of the Bucks’ arena doesn’t mean other cities should immediately open their wallets to billionaire owners. The most important part of the Milwaukee plan was how it was structured - with the owners putting in $250 million of their own money, $80 million from the state was a pretty small ask. The state regularly builds government buildings that are more expensive.

Had the state offered up, say, $250 million for the arena, the “jock tax” wouldn’t be nearly enough to cover the investment, much less turn such a huge profit for the state. At that point, it would be up to formulas to determine the ancillary economic impact from the arena, which are far tougher to measure. (And other cities probably wouldn’t win an NBA championship because they probably don’t have two-time league MVP Giannis Antetokounmpo.)

Take, for example, the NFL’s Buffalo Bills, a team asking New York taxpayers for over $1 billion to build and maintain a new stadium. It will be the 19th new NFL stadium built since 2000, 16 of which used public money. All total, these publicly-funded stadiums have cost taxpayers a combined $7.3 billion.

There’s good reason to question whether these massive investments are making any difference. In a research paper released just this year, a group of university researchers analyzed over 130 instances of publicly-funded sports venues and found “very limited” economic impacts.

And this is where critics of public stadium financing get their ammunition - in terms of economic effects - i.e., people spending money downtown, buying jerseys, paying for parking and the like - the benefits may not override the cost. Vendors in Buffalo will have to sell an unheard of amount of chicken wings to collect $1 billion in sales taxes.

But with smaller projects like Fiserv Forum, there is a direct monetary benefit to state government attributable to the project. If you’re a conservative who would rather the state not have the extra $10 million to spend, then fine - although legislators are more likely to raise taxes to support that spending than actually cut $10 million from the state budget.

Critics of the plan at the time argued that if the Bucks were to move, the “jock tax” revenue wouldn’t dry up, it would simply be shifted to other businesses where people would spend money absent an NBA sports team in Milwaukee. But this analysis is incorrect in that it confuses the apples of economic impact analysis with the oranges of player income tax revenue.

It is true that if the Bucks were to leave, people would spend their entertainment dollars in other businesses that also pay taxes. But the loss of income tax revenues from NBA players is a clean loss. LeBron James’ salary is set - the state only has to decide whether they want a portion of it. Otherwise, that income tax will go to Seattle or wherever the Bucks play next.

Skepticism of big arena plans that benefit rich owners is always warranted. It is my default setting. But this specific plan - misunderstood by much of the national media at the time - worked even better than expected, and the state is better off for it.

ALSO: In one of the most incredible media coincidences of all time, the Los Angeles Times in 1969 ran two stories next to each other on the front page that are are eerie in retrospect.

On August 17, the paper ran a story about the recent Sharon Tate murders and placed in on the right side of the page. Just to the left of that story, the Times ran another piece about a group of hippies who had just been arrested for car theft.

It would be months before the police figured out the people in the story on the left were responsible for the horrors of the story on the right.

A few corrections:

- It was the NBA itself that was demanding the arena/move (and hoping for the latter). Indeed, that the team would be moved if a new arena was not built was written into the NBA's acceptance of the sale from Herb Kohl to Wes Edens and Marc Lasry.

- The $250 million was the cap on government/quasi-government involvement, not Edens'/Lasry's involvement. They were on the hook if the project went over budget.

- $500,000 of $4,000,000 is 12.5%, not 25%.

Your analysis also doesn't cover the city's and county's contributions. While the city and county contributed less than the state and the convention district (which is in a bit of a cash crunch itself as it had to delay once again the final phase of the convention center), they have no real source of compensation because there is (thankfully) no local income tax and the land is exempt from property taxes.

The true uniqueness of the Bucks/Fiserv Forum situation is not how it was structured (though that the ownership group and not government would be responsible for overruns was unique); it was the guarantee from the sports league of a move rather than a mere threat from the ownership.